Terry Wallis

Originally published in Arkansas Life

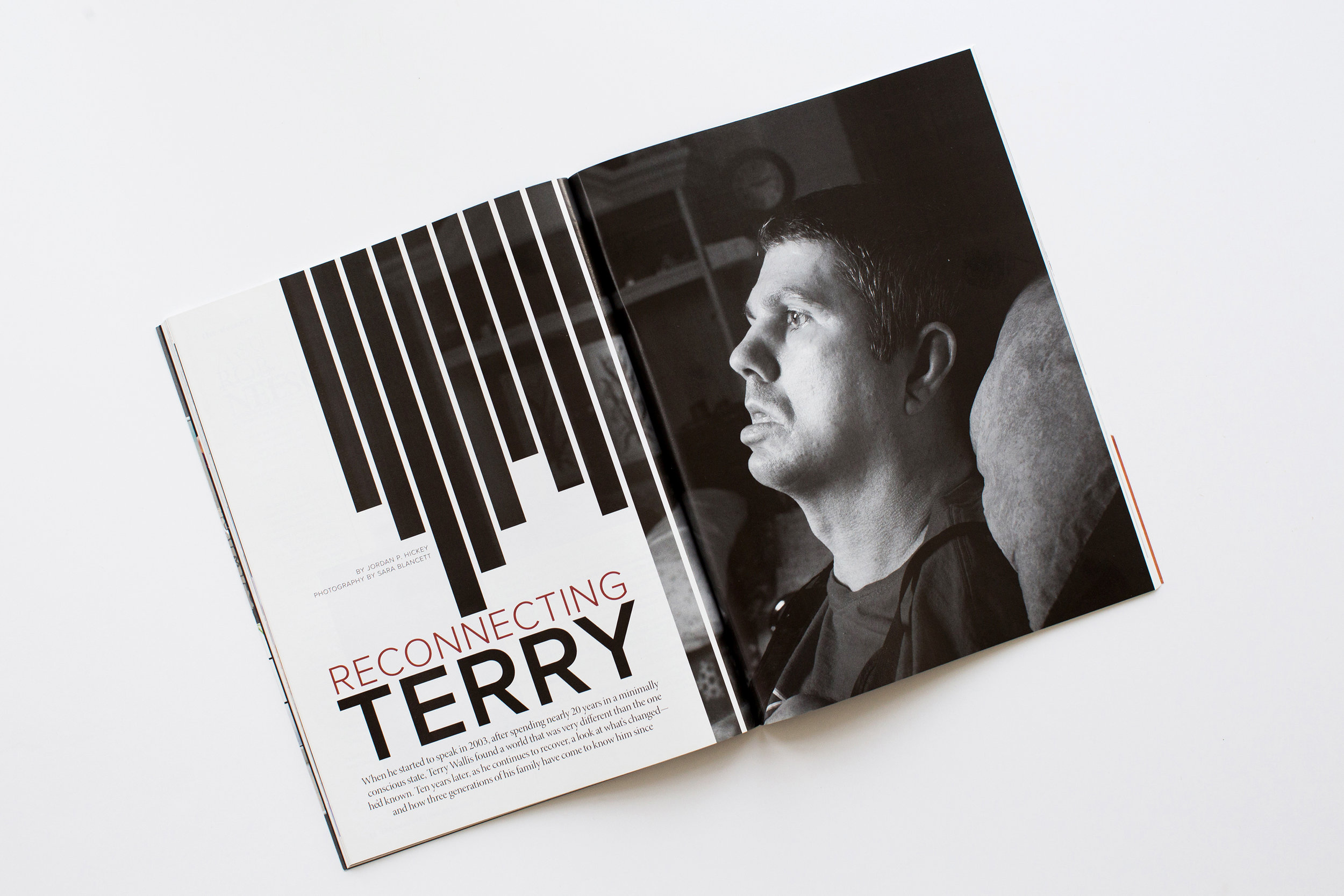

Reconnecting Terry

In 2003, Terry Wallis spoke for the first time in two decades. Now, aided by his family, he's finding his place in the world

By Jordan P. Hickey | Photography by Sara Reeves

IN THE ROOMS THERE WERE CONSTANTS. Blue and white walls, the subtle though unmistakable hints of routinely applied disinfectant. A reliance on fixed schedules and protocol endemic to assisted living. And every other weekend, and sometimes more often, there was a small woman who, despite the regular turnover of staff at the nursing home in Mountain View, was well-known. Though she’d aged in the 20 years she’d been pushing her way through the doors, heading off down a corridor, she still looked very much the same: large eyes made larger by large glasses, brown hair pulled into a ponytail. It was like she’d always been there, coming to see her son who didn’t speak. He was a man who’d only known 20 years, who’d seen his daughter grow to 6 weeks and no older, whose life—interrupted as it had been by a car accident—had been lived out in the days, hour by hour, where the walls seldom changed. His only expressions of personality were buried in whatever interpretation his family managed to glean from the blinks and grunts and fits that came through what would later be described as a minimally conscious state.

And because his family members weren’t altogether certain what was making its way through, they assumed everything was. Twice a month they brought him home, where they’d take him down to the creek or go squirrel or deer hunting because those were things he had enjoyed. They attended family reunions and played country music—his favorite—over the radio around the clock. He was part of their lives, albeit only to the extent that his physical condition would allow.

Over the years, all those constants were smoothed, streamlined and refined by routine. And after so many years of the same, after a lack of responses to so many observations and comments and questions, there was little reason for his mother to think anything would be different when she stopped by one June afternoon. As she walked through the doors, an aide asked him who she was. And to that largely rhetorical question put to him so often in the nearly 20 years he had been silent, he responded: “Mom.”

*

TEN YEARS LATER, on an August afternoon at a place called Round Mountain, northwest of Timbo and just west of Mountain View, there’s calm for a while, and then there’s motion. Cars arrive licked with belts of rust-colored dust that make it seem as if they’ve just emerged from pools of the stuff. Cars slip from the edges of the red-dirt drive and probe their noses onto the grass, parking sideways and slantways toward the house. Cars fill the gravel drive leading to the house, and once that’s filled, crowd along an elbow of road beneath the sign that identifies the place as Wallis Farm. Stepping from their vehicles as they’ve done so many Friday nights before, people wander up the drive, mingle in the yard, veer off to the detached garage to play pool or make their way up the concrete steps leading to the front door. Motion is everywhere.

And inside, there’s music.

Played by a five-piece band, twangy, throaty country tumbles from the family room into the dining room, suffusing the small space, drawing no shortage of toe-tapping and finger-drumming from the handful of people cresting the last waves of middle age, spaced evenly around the wooden curves of an oval kitchen table. At the head of the table farthest from the band is an older man with narrow eyes and a sloping jaw. Pasted to his lip is a hand-rolled cigarette plugged with a handmade filter made of toilet paper. His name is Jerry Wallis, and he’s sitting beside his wife, Angilee, who draws store-bought Pyramids from her pack on the table.

From where she sits, elbows on the table and hands clasped, Angilee can see everything in the dimly lit living room. It’s a space crammed with musicians, as well as amps and a drum set, permanent fixtures even when the musicians aren’t. Sunken couches line the walls below family photos of her four children when they were teens. Every now and again, however, she looks away. Dropping her elbows, she pushes away from the table and wheels back in her chair, fingers locked on the lip of the table, glancing through the door behind her to look at her eldest son, Terry.

The lights in his room are off, and it’s mostly still. Once a garage, the room has high, broad walls sparsely decorated with photos, encouraging letters, prayers and a bouquet of three $1 bills pinned just above his bed. Eyes aching, bobbing listlessly to the music, he’s lying between the sheets. When the band plays “Lucinda,” he lolls his head side to side to the extent that his body will allow him, saying “All right” in the breathy manner his speech has assumed. His words slip out hoarse and somewhat slurred, and for someone who’s just met him, it can be difficult to grasp what he’s saying.

As the band starts a song called “Linda,” he becomes upset, remembering a time years before when he dated a girl named Linda, and seems to think the man singing (his brother, Perry), has intentions of moving in on her—this despite the more than two decades that have passed since the couple dated, and the fact she’s since moved to Fresno, Calif.

Unremarkable as it might seem, such response from Terry would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. For nearly 20 years—from July 1984 to June 2003, following a single-vehicle accident when the white Chevy LUV he was driving skidded off a bridge into a dry creekbed midway to Marshall, leaving him in a coma at the age of 20 and killing the boy he’d been with—he’d remained in a minimally conscious state. For nearly 20 years, no one had heard his voice.

Then in 2003, he started to speak.

Even a decade after his neurons crackled to life, reminders of the world’s response are still spread throughout the house. In an accordion folder in the dining room, there’s a copy of the study done by a team of neurologists showing re-established neural pathways in the back of his brain. Sheathed in a Plexiglas holder on a desk in Terry’s room, there’s a letter from then-Gov. Mike Huckabee, praising him for his strength and patience, and his family for their support. Overlooking the kitchen is a canister that once contained a bottle of top-shelf whiskey, delivered from a Hollywood Studio that was considering making a film about his life story. For months after Terry started to speak, news of his recovery drew reporters from all over the globe down the red-dirt road where the family lived. They told about his love of Fords and his insistence that Reagan still held office. How his first word was “Mom,” followed closely thereafter by “Pepsi” and “milk.”

But for all the attention focused on the family during those months, the nature of the news cycle limited the scope of what the reporters saw. What was scribbled in notebooks and captured on film were a series of moments—poignant and telling, to be sure—but only glimpses of Terry’s life as it was during the early days. They didn’t show what it was like for members of his family—three generations—as they have gotten to know the man he is now.

For them, those relationships can be described in conventional terms—grandfather, father, son—but the way they’ve been realized and the role Terry plays in each person’s life is not. Each has known him differently because each relationship started at a different time— before his accident, after his accident, after he started to speak—and is accompanied by its own set of baggage. And, for all the stillness in the house, for all the slow passing of time when some things seem to have become frozen in the past, the truth is, there’s constant motion. There’s movement every day.

*

AS IT GETS LATER and the stained-glass blossom above the front door starts to dim as the sun dips behind the hills, more people arrive until the entire circle drive is crowded with car after truck after truck. Among the new arrivals is Terry’s granddaughter Tori, 9, who’s come from her house just up the road and, having found a cadre of younger children who follow close behind, walks in and approaches the head of the table as the band plays. She has lank blond hair and dark circles beneath her eyes, and she wears a long-sleeved shirt with narrow purple and white horizontal stripes. She is tall and thin, and walking through, she says matter-of-factly, “I want to see Paw Paw.”

Edging in behind Angilee, her great-grandmother, Tori stands for a moment at the threshold of the pink-curtained door and, hitching up her jeans with a tug at her waistband, steps around the pneumatic lift and on down the two unpainted stairs to see her grandfather, Terry. Entering the room, she turns on the lights so she can see him. In the bed, he looks younger than his 49 years. His hair is cropped short around the crown of his head, stopping well above his eyes, which are large and brown. In his hair there are patches of gray that have appeared in the past 10 years. Scrunched tight against his chest is a small stuffed rabbit that must have once been white but is now discolored, threadbare and faded.

For the past several days, he’s been feeling under the weather; his eyes have been bothering him. To see him there is a reminder that, no matter how miraculous it all is, he is still recovering, and there are still many aspects of his life that merit concern. He has to be turned every two hours to avoid bedsores. He can only handle direct exposure to the sun for 15 minutes before red splotches appear and spread over his skin. His lungs are especially susceptible to infection because he can’t cough voluntarily, and so he must wear a special vest that pounds his chest to loosen the congestion. He has a device (which he despises) that sprays medicine into his face at intervals to help with his breathing. His drinks have to be thickened to the consistency of honey.

For Tori, standing there before him, this is the norm, although she’s been known to ask why he is the way he is, her grandfather, the man she’s always known. He’s the man who is kind and will say “yes” to most any entreaty she puts to him, and who will gladly agree to change the channel on the television in his room, even when he’s watching “Gilligan’s Island” or “The Beverly Hillbillies.” And even if her friends balk at spending much time around him on those weekends when her mother, Amber, brings him to their small home just up the road, Tori has no qualms about taking the cot beside him and talking to him through the night.

He doesn’t always remember her name, but that doesn’t seem to faze her.

There are times when he does remember because there are good days, and there are better days. With every passing year, he’s improved, taking a series of baby steps that, while seemingly insignificant and difficult to detect even as they happen, are remarkable in their own way. Within the past year and a half, for example, he’s started to make decisions. He knows more words. He can spell hippopotamus—or at least the first half (ending the word by saying “-potamus”). He knows dates and names. There are even times when a new expression moves across his face, his brow furrows, and you can see wheels creaking into motion. It’s very clear: He’s trying to think.

*

SITTING THERE, SHE’S she’s deeply tanned—a color that doesn’t suggest leisure or a tendency to frequent tanning salons as much as it does long hours spent outside. It’s not surprising to learn that she spent the past Saturday at a nearby rock quarry, hefting stacks of rocks from one pile to another, this despite the fact that she recently gave birth to her second child, Blazen Lawayne. Her hair, clearly dyed previously to different shades, hangs in strings across her forehead and into her eyes.

When asked about him—how he’s changed in the nearly 30 years that she’s known him—her stories come in fits and starts. How her first memory of him, admittedly, was one of fear, when at age 4 or 5, she saw his flailing limbs as he was in the throes of a violent fit at a family gathering; and how she managed to deal with those feelings by promptly walking outside. She can remember praying for him often when she was young. She would pray—and daydream—that with a knock on the door, the man in the photos would re-enter her life, as though he’d always been there. Smiling, moustached, his dark eyes revealing the same rebellious and stubborn streak Amber recognizes in herself, he’d be the man from the stories she’d heard the family tell about her father when he was a young man.

They’d tell her about that time when he attached a boat motor to the back of his car with the intention of driving the contraption across Lake Frierson. (As she remembers hearing, he got caught before it really got going and was subsequently banned for life.) He despised rock ’n’ roll, and, older brother that he was, refused to let that stuff get played from any radio within his hearing. There were stories about how whenever his brother Perry found a nice girl that he liked, Terry was there, swooping in with a preternatural sway of persuasion, and convincing her she’d be better off with him. There were feuds and fights and some tenderness thrown in for good measure, all of which, when she heard those stories told, made Amber realize that she was very much the man’s daughter. It was of some consolation that the genes she’d received from him had been preserved with such fidelity.

“You know, it’s weird because you know that I never knew my dad as a person before his wreck, but I’ve had so many people tell me that … to be so much like him, it’s just ridiculous,” she’ll say later. “The wittiness, the sense of humor, the mischievousness. That’s all genetic, come from my dad, because I didn’t ever know how he was.”

Those ideas, however, stood in stark contrast to the man she knew. The father she’d built up in her imagination and prayers wasn’t—couldn’t—be the one who was in her life. For one, there were those physical limitations to speech and movement and communication imposed by his condition. But also because he wasn’t an everyday fixture in her life the way many parents are. Six months after the accident, her mother, Terry’s wife, had left Round Mountain—she’d left a note saying she had a life to live, that the idea of living that life alongside a comatose husband just wasn’t in the cards—and she’d taken Amber with her. They periodically returned (for holidays, or when they were moving from one place to another and passed close to Round Mountain), and it was during those infrequent visits that Amber had come to know her father to the extent that was possible.

They’d come to her maternal grandparents’ house just up the road, and she’d sit beside him, reciting the alphabet and basic math problems, telling him about her day, about what was going on in her life.

“I knew he knew something because when I’d ask him ‘What’s two and two?’ and when I’d say “Five,” and he’d blink his eyes once for yes and twice for no, or twice for yes and once for no—I can’t remember—he’d blink it out right,” she says. “And I could say, ‘Is it four?’ and then he’d blink for me. I’d say, ‘Is it seven?’ and he’d blink for me. So, I knew that he was smart and that he was in there. I just didn’t know much else besides that.”

With only the barest profile of emotion and personality mute in her father’s form, every blink and grumble became a suggestion of something more. But as she hit her teen years, the fantasy world—the dreams of seeing him smiling and standing there at the door—yielded to reality. She began to focus more on the life that was going on around her.

The young family had moved frequently and erratically, and grew quickly after her mother left Round Mountain. There were the issues with the Department of Human Services. There always seemed to be a lack of electricity or lack of water where they stayed. As she grew older—and memories became blurred—there were some issues with disputing authority figures, including one particularly memorable incident when she was living with her aunt Tammy that involved some pot, a drug dog and a carpet covered in cayenne pepper.

But all of those stories, however, led to one moment.

She tells the story about how she’d been living in Jonesboro, having left home at 16, subsisting on a diet of McDonald’s cheeseburgers and Mountain Dew, when she got a call. The voice on the other end of the line was her uncle Perry. He said her dad was talking. Still skeptical, she drove that afternoon to the Mountain View nursing facility where he’d spent much of the past 19 years. She walked into his room. He told her that she was beautiful. She walked out of the room and slumped into a chair outside the door and wept.

*

ON THE DAY HE started talking, Angilee remembers, the room at the nursing home was spacious. It was the same as it had been for nearly 20 years—since he had the accident—and there were tables and a nurse’s station, and a worker in the kitchen. To describe much beyond those general specifics is difficult, however, as most details have been swept up and lost in the events of that June afternoon. Specifically, lost in a word: “Mom.” When she walked into the great room and heard that word, it wasn’t said in the voice Angilee had been aching to hear for so long. It was somewhat muffled, a voice that had disappeared into itself for nearly 20 years before answering what had essentially been a rhetorical question.

“Who’s that old lady?” Angilee remembers the nurse’s aide saying with a laugh.

“Mom,” her son said. She looked at the woman and then at Terry. They were equally startled. The very idea of him speaking after so many years of being told there was very little hope of him recovering was enough to stun anyone, but to hear it was just—there’s not a word for it. Even today, she’s at a loss for how to express what she felt that afternoon, taking a stab by saying “happy” and “shocked,” though neither of those, nor any describable emotion, really comes close.

For the next several hours, she sat with him as a carousel of incredulous staff and visitors came by to hear his voice for themselves, asking any sort of question that might elicit the word “mom.” She left that afternoon and went first to the home of a co-worker who lived nearby, just because she needed to tell somebody—anybody—before driving the 26 miles home to tell the rest of the family.

They brought him home that weekend, and as had been her custom for many, many years, Angilee spent Saturday morning with him. He was in the living room of the little house, and from where she stood at the stove, she asked him what he’d like to drink for breakfast. He answered: “Milk.” A few days later, when they brought him back to the nursing home—it would still be weeks before they could bring him home for good—the staff asked him when his birthday was, and he answered.

In the years that followed, Amber and Angilee have started to understand the man Terry is now. They no longer have to guess what he’s thinking. With every word he says, he becomes more and more his own person, gradually replacing the father and the son who had lived most vividly inside their heads for decades.

Yet, there are differences in the way Amber and Angilee know him. Because Amber had only known him in the aftermath of the accident, it’s almost like he was a blank canvas—every word and expression has helped shape the person she’s come to know over the past 10 years. For Angilee, however, it’s not quite the same. She raised him—she already had the painting. When he started to speak, she had to accept the things that were different about him.

This became especially clear when her daughter, Tammy, gave her the book Stroke of Insight. It’s the memoir of Jill Bolte Taylor, a Harvard-trained neuroanatomist who after having a massive stroke made a full recovery over the course of an eight-year period. The book walks the reader through what it’s like to live that way, what people in that condition are experiencing and what their loved ones can do to help—something made especially clear by the chapter called “What I Needed Most.”

“I desperately needed people to treat me as though I would recover completely.”

“I needed people around me to believe in the plasticity of the brain and its ability to grow, learn and recover.”

“My brain needed to be protected and isolated from obnoxious sensory stimulation, which it perceived as noise.”

However, perhaps one of the most striking sections of that chapter is when she writes the following: “[Because] of my trauma, my brain circuitry was different now, and with that came a shifted perception of the world. Although I looked the same and would eventually walk and talk the same as I did before the stroke, my brain wiring was different now, as were many of my interests, likes and dislikes.”

And much like the doctor in the book, there are things Angilee notices that are different about Terry—subtle things that exist below the surface. Her son is not entirely the man he was before. He’s mild-mannered and soft, she says, in a way that never characterized the teenage and young-adult version of Terry. The stubbornness and obstinacy of personality and character have been wiped away. But even then, as Angilee and Jerry say over coffee and cigarettes, there’s still so much they’re learning.

“We’re still finding out things about him,” Angilee says. “Right after he started talking, there wasn’t much you could really pinpoint because we didn’t know.”

“He didn’t make a statement,” Jerry says. “If you asked him something, he might answer you. But as far as him just coming out with an idea of his own out of the blue, he didn’t do it, and still doesn’t, much. It’s new to us now when he does.”

“He was so inconsistent, you really couldn’t tell what he was thinking,” Angilee says.

“There was something kinda peculiar, though. There would be a time late at night, usually late at night, a certain time when he would seem normal, almost completely normal.”

“Right.”

“What would you say? Five minutes?”

“Sometimes longer than that.”

“Until something broke the streak, wasn’t it?”

“I mean, he still, like when asked about the date, the year? It’s like, just for a little bit, it’s like he’s there completely,” Angilee says, “but if you break that train of thought …. Like, I used to try to get him on tape, you know, some of the things he was saying. But if I’d leave and come back, then it’d be gone.”

When she’s asked if they’re any closer to understanding the person Terry has become, Angilee says, “For me, trying to figure it out is kinda like … kinda like the way you can’t answer questions. You can’t answer questions. It just sorta scatters if you try to get it all bundled. As Jerry would say, too many limbs on the tree. It goes in so many different directions. I mean, it’s still … it’s still like that. Because he’s different from one day than he is the next day. Still pretty much the same, but still different.”

And even if there are some traits that have been carried through the years—through the long states of inactivity and something that resembled sleep but was so much deeper—and manifested in characteristic quirks like Terry’s oft-repeated appreciation for Pepsi and American-made cars, other traits have changed. Some have been excised and others have been added. Nowadays, for one, his father is never wrong, when before they were constantly clashing, to such an extent that Terry had left home when he was 16.

To spend time with Terry, however, is to realize there’s an awareness that at first, second, third glances may not be apparent—like a cork bobbing beneath the surface—but which appears in full when a joke is cracked, and he starts laughing, head lolling, the glimmer of total understanding there in every hoarse and breathy laugh. And it’s in the way Angilee speaks about her son, who almost seems to have been three different people through the years, and the way that there are oftentimes glimmers of someone else, someone who asks what year it is and wants to know just how old he is, that she knows there’s more there than meets the eye.

“When you get to thinking … well, I don’t really anymore, but I used to—I was real bad about thinking about, ‘Well, I wonder how he would be if he had not wrecked?’” Angilee says. “And that person is gone. Just like it said in that book. That person that he was before is gone.”

“Yeah, but there’s a lot of him that’s still here,” Jerry says.

But it’s not, Angilee replies, as she tried to pinpoint a reason that she can’t keep looking for those threads connecting Terry to his past.

“Because I know that it can’t be” she says, eventually. “I know that person he was before can’t be. No use in even thinking how it might be because you just have to go on with what he is. You know?”

*

ANGILEE ALREADY HAS her eyes closed. Jerry sits at the head of the table, eyes open, in front of the cake, a miracle of butter cream and three layers of lemon, strawberry and lemon made for the occasion—his and Angilee’s 50th anniversary—by a friend up from Pine Bluff. It’s only once he’s been assured the surprise “is not gonna bite” that Jerry finally closes his eyes. The family closes in around the couple, phones and cameras at the ready as a large grandfather clock is lopsidedly hefted inside and set upright. It’s a beautiful clock, with a boxy head and narrow stem. The family fawns over it; then photos are snapped, with brief back-and-forths as family members coax Jerry to smile.

“Smile like you love each other,” says a niece.

“You’re a good pretender,” Angilee says as Jerry cracks a smile.

“Smile like you just won at cards,” comes a second invocation.

As the evening progresses, the couple read cards congratulating them on their golden anniversary with titles like “For a Special Couple.” Angilee, dressed in a brown blouse with white lace around the neck, is sitting in her chair beside Terry, who is wearing white socks with gray toes, khakis and a blue Corona shirt. He seems tired.

“Whoa, foot,” Angilee says as Terry’s foot, white sock with gray toes, enters one of the fits of spasmodic jiggling his feet are prone to. “Whoa, foot,” she says again, her hand on his ankle and eyes on his face, whose eyes are looking through the roof of the house to some realm known only to him.

Later in the evening after dinner has been served, Tammy asks Angilee, “Mom, you want me to getchoo a plate?” She responds, as she helps to feed Terry ground-up pork that resembles sawdust, mac and cheese crushed in it, that she’ll get something in a little bit. Amber then takes her place and starts to feed Terry what’s left, as another country song floats through from the living room. She moves a plate of food to avoid knocking it over.

Although much of what Amber says to Terry and the things he says in response are largely overwhelmed by the nearby conversation at the table, during a lapse in chatter following a yankee joke, it’s possible to catch a little bit. “That taste good?” she asks as she draws back the empty spoon. She looks beyond him to a group of photos hung on the wall below a .223 rifle. She leans forward, then takes the frame off the wall before asking her dad, “D’you see someone put an ugly photo of me in this frame? They coulda just left me out.”

He looks at her.

Truth be told, for someone looking in, it’s difficult to understand what is conveyed by that look. But for Amber, although the way she knows him continues to shift from day to day, this is the norm. Because in those 10 years she’s come to know him, every spoonful fed at his bedside, with every fragmented word and every hoarse laugh, there’s the one indelible fact that galvanizes the bond stretched between them: No matter how it might seem to the outside world, for as much as Terry has changed these past several years, there’s even more about him that has stayed the same. He’s still the son, father and grandfather his family has always had. No matter how he speaks, thinks and responds, he’s still the same person.

He is Terry Wallis and always will be.